The Carbon Ring Crisis

Archery seasons are wrapping up and most of the country is staring down the barrel of rifle season. I shoot my rifles year-round, but like some of you, I get hyper-sensitive to rifle performance before Fall.

I have three go-to-rifles: a 22 Creedmoor in a fiberglass adjustable K2 stock for coyotes, a 28 Nosler in a carbon fiber Chalk Branch stock for elk, and a 6.5 PRC for antelope, deer and when I’m guiding kids.

That rifle, which is built on a medium-length action, is currently in a factory stock, but I have a carbon fiber K2 on order. AG Composites is building it with a shorter length of pull to better fit the kids that often shoot it.

The 22 Creedmoor and the 28 Nosler shoot hand-loaded ammunition, and I mostly feed the 6.5 PRC a steady diet of Hornady Match.

When to clean a rifle

There’s no clear-cut answer on how often a rifle should be cleaned. I know from experience that my 28 Nosler shoots best if I thoroughly scrub it out every 50 rounds. My 22 Creedmoor held one-hole groups to about 250 rounds with only mild cleaning now and again.

How often a rifle needs to be cleaned will depend on how overbore the rifle is, which powder you’re shooting, the bullet you’re using, and how picky your barrel is. I’ve found that a little carbon or copper fouling in the rifling likely won’t impact accuracy or speed. But a lot of fouling will, especially thick carbon fouling in throat of the bore.

My theory – for better or worse – on cleaning precision rifles is “I’ll clean the rifle when it tells me it should be cleaned.”

This approach works, so long as you remain attuned to the indicators. The number one indicator is pressure sign: are you getting ejector swipe on your case heads or are you experiencing heavy bolt lift after firing?

Each of these cases is shows ejector swipe near where the headstamp reads “.22”

Observing pressure sign is one way hand-loaders can tell they’ve created a load that’s “too hot,” but if you have a load that’s always been safe in your rifle and it suddenly starts showing pressure sign, there’s a good chance that your bore needs to be thoroughly cleaned.

There are other signs, too. Performance indicators include the rifle speeding up or slowing down. Of course, this only works if you’re using a chronograph at all times. Since purchasing the new Garmin Xero chronograph, I never shoot at the range without recording muzzle velocity. If you don’t have a chronograph, another indicator is reduced consistency/accuracy (larger group sizes).

Finally, in extreme examples, a thick carbon ring can develop in the throat of the barrel and impact the cartridge’s ability to enter the chamber. Even if there’s no issue chambering a round, a thick carbon ring can still be present.

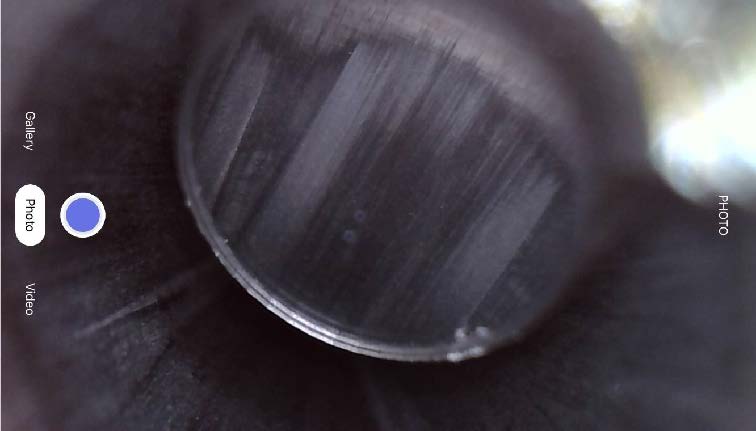

Unfortunately, the only way to know (aside from chambering issues) is through the use of a bore scope. Bore scopes used to be expensive and clunky to use. That’s no longer the case. I purchased a Teslong flexible bore scope for about $90. That’s been a game changer. It emits a WiFi signal, and the user links to it with a phone or an iPad to view the inside of the bore.

Critical failure

I once learned the hard way that two of my rifles were way, way too dirty. At the time, I wasn’t paying as much attention to pressure sign and group sizes as I should have been. This was the case with both my 22 Creedmoor and my 6.5 PRC.

In both scenarios, I closed the bolt on a loaded round, ignoring that the bolt closed with some resistance. I did not fire the gun, but instead, opened the bolt with a loaded round in it. The handloads in the 22 Creedmoor have very little neck tension, so the bullet got stuck in the barrel without my realizing it. The brass case came out of the action and powder went everywhere.

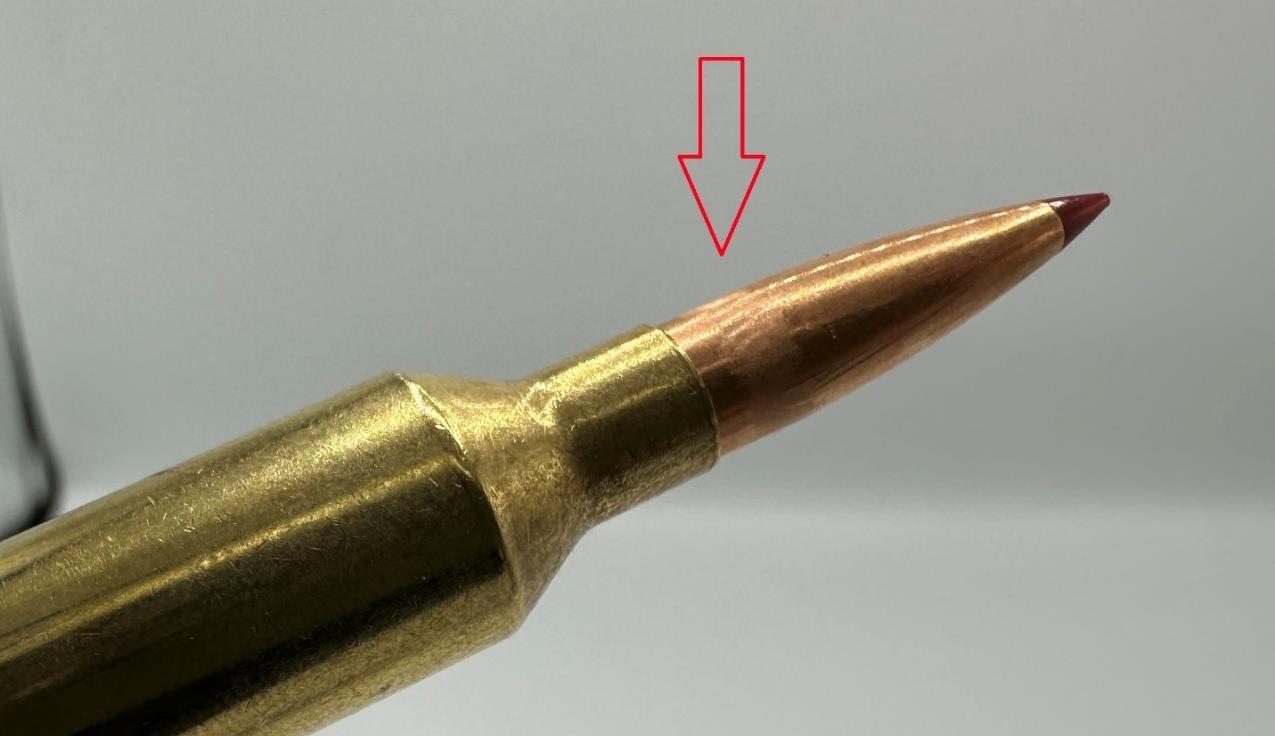

With the 6.5 PRC, I had to pound the bolt open, so I was very much aware of an issue. If I had been trying a hand load that I’d never fired before, I would have assumed that the bullet was seated too far out of the case (beyond SAAMI spec), causing it to lodge in the rifle lands when the bolt was closed. But both loads were confirmed to fit in my guns with some freebore remaining. Plus, the extracted bullets did not have little dimples from being stuck in the lands. Instead, the exterior surface of the bullets had been abraded across a 360 degree ring around the circumference of the projectile, almost like they’d been sanded with fine grit sandpaper.

The abraded ring on the surface of the bullet came from the projectile being jammed into a thick carbon ring.

Once the stuck projectiles were freed from inside the rifle bores, I borrowed a bore scope and confirmed my suspicion: a thick carbon ring had developed in the throat of both rifles. I didn’t think a carbon ring could build up to that extent, but there it was. They were so thick that they kept the bullets from extracting.

Borescope photo of the throat of a rifle bore showing moderate carbon fouling and the early formation of a carbon ring at the beginning of the lands.

This happened after about 200 rounds on my 22 Creedmoor and 300 rounds on my 6.5 PRC. Now, keep in mind that those numbers are total round count. It wasn’t as though the rifles had never been cleaned. They had been. They’d just been cleaned ineffectively. And again, I’d been negligent about watching my group sizes because I primarily shoot steel targets at long range. Both these rifles are capable of 1/4 -minute groups when I’m shooting well, and they’d opened up to 1/2-minute and 3/4-minute, respectively.

The issue was the manner in which the rifles had been cleaned. Digress. I had been wiping them out with Butch’s Bore Shine or using several cycles of Wipe-Out foaming cleaner. I typically did this until my patches came out clean, but I never used a brush. I bought into the marketing hype that solvent and patches were sufficient. I learned the hard way that it’s not.

A deep clean

So, I did what I always do when confronted with a problem I’m not sure how to resolve; I ask someone with more experience. A friend of mine who shoots thousands of rounds through his bolt action rifles each year invited me over to clean one of my guns. He introduced me to the ThorroClean bore cleaning system, which includes a cleaning compound and a flushing solution. Using these in conjunction with nylon bore brushes, I was able to completely remove the carbon rings from both rifles and resolve all my issues.

It took about 75 brush strokes though the entire bore and an additional 75 strokes concentrated on the throat area to get the barrels spotless. I’m not afraid to change directions of the brush inside the bore if the brushes being used are nylon. I avoid the use of metal brushes entirely. The brushes I use are manufactured by Iosso.

There’s nothing wrong with simply wiping a bore out with solvent, but patches and solvent aren’t enough. If you don’t use brushes or a mildly abrasive compound, you’re relying on a chemical reaction to strip copper and carbon fouling out of a bore. Brushes and compound physically remove those deposits. After brushing, I noticed hard, shiny flakes of carbon on the patches I ran though the bore. That was evidence enough that the carbon was coming out.

After thorough cleaning, I ran the borescope through the guns again, and the bores glittered like diamonds.

Borescope photo of a spotless rifle bore after 75 strokes with a brush covered in ThorroClean.

My tight groups came back, my speed stabilized, and the pressure sign disappeared. No more pulling bullets from cases.

Maybe you’ve always cleaned your guns thoroughly, but I did not. I hope this helps someone.

By Dan V., Transient Outdoorsman